The 1967 Chrystie St Connection marked a new era for the NYC Transit Authority (TA) in terms of subway construction—at least the attempt at such. Following the connection, in 1968, came the Program for Action, which included plans for the construction of the Second Avenue Subway, 63rd St Tunnel, Queens Super Express, and the Archer Ave Extension.

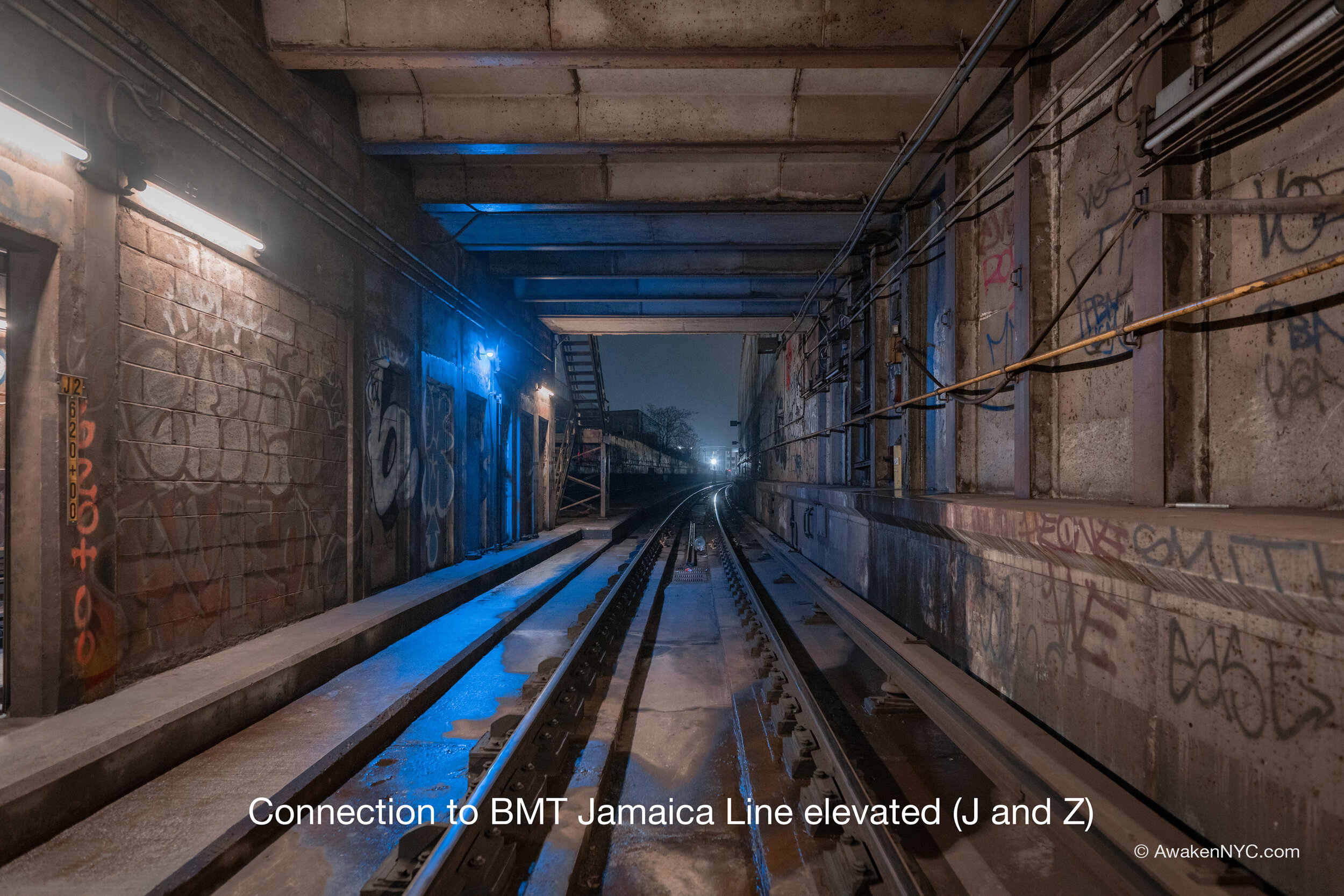

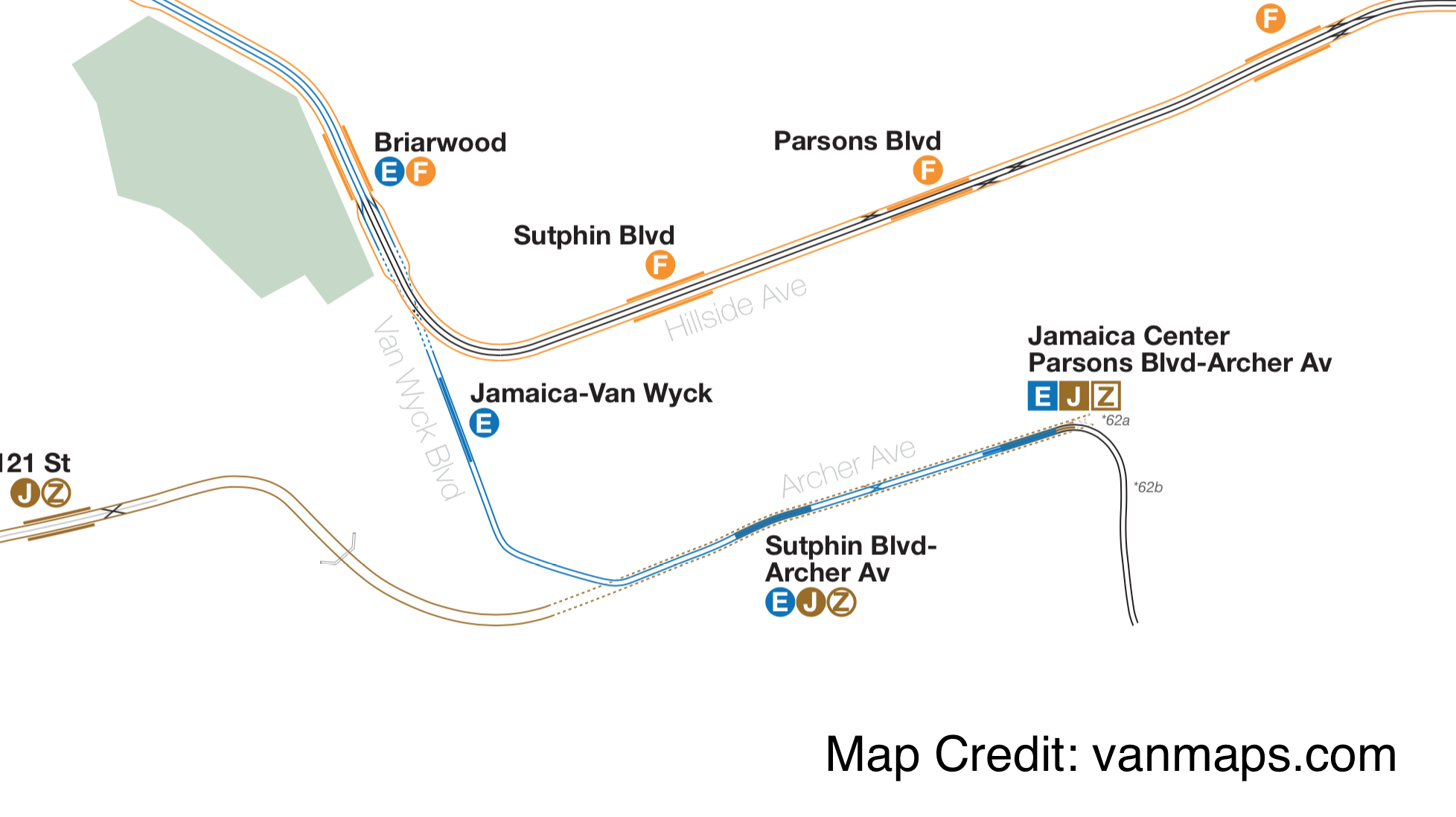

The Archer Ave Extension was built through many scandals and much political and economic turmoil as the City and TA slogged on through the ‘70s and ‘80s, a notoriously rough time for New York. The Extension brought three new stations: Jamaica—Van Wyck, Sutphin Blvd, and Parsons Blvd—Jamaica Center. It includes two levels, with the upper level for IND Queens Blvd Line trains (the E line) and the lower level for BMT Jamaica Line trains (the J and Z line). For the BMT line, it would partially replace an elevated line that had been demolished.

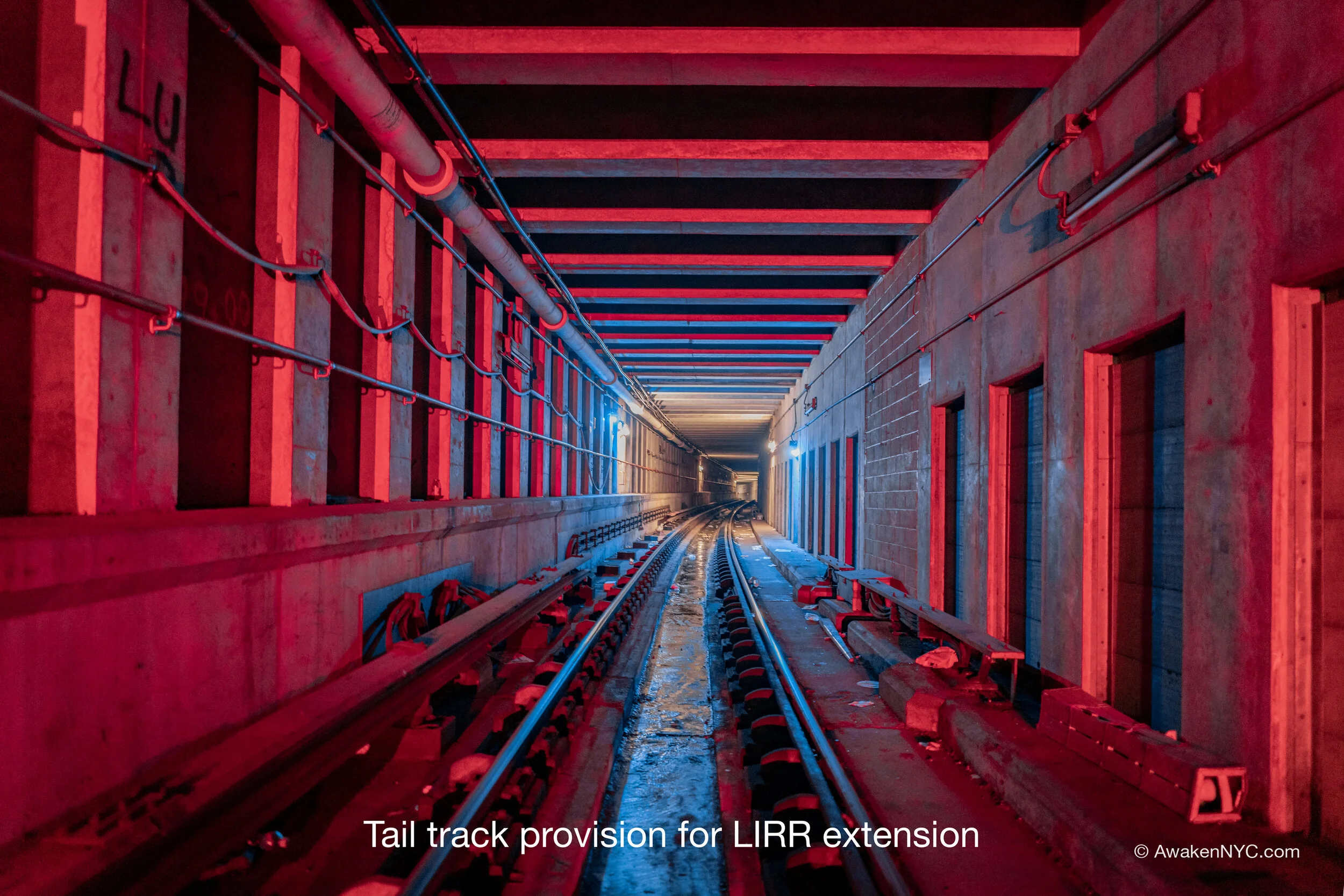

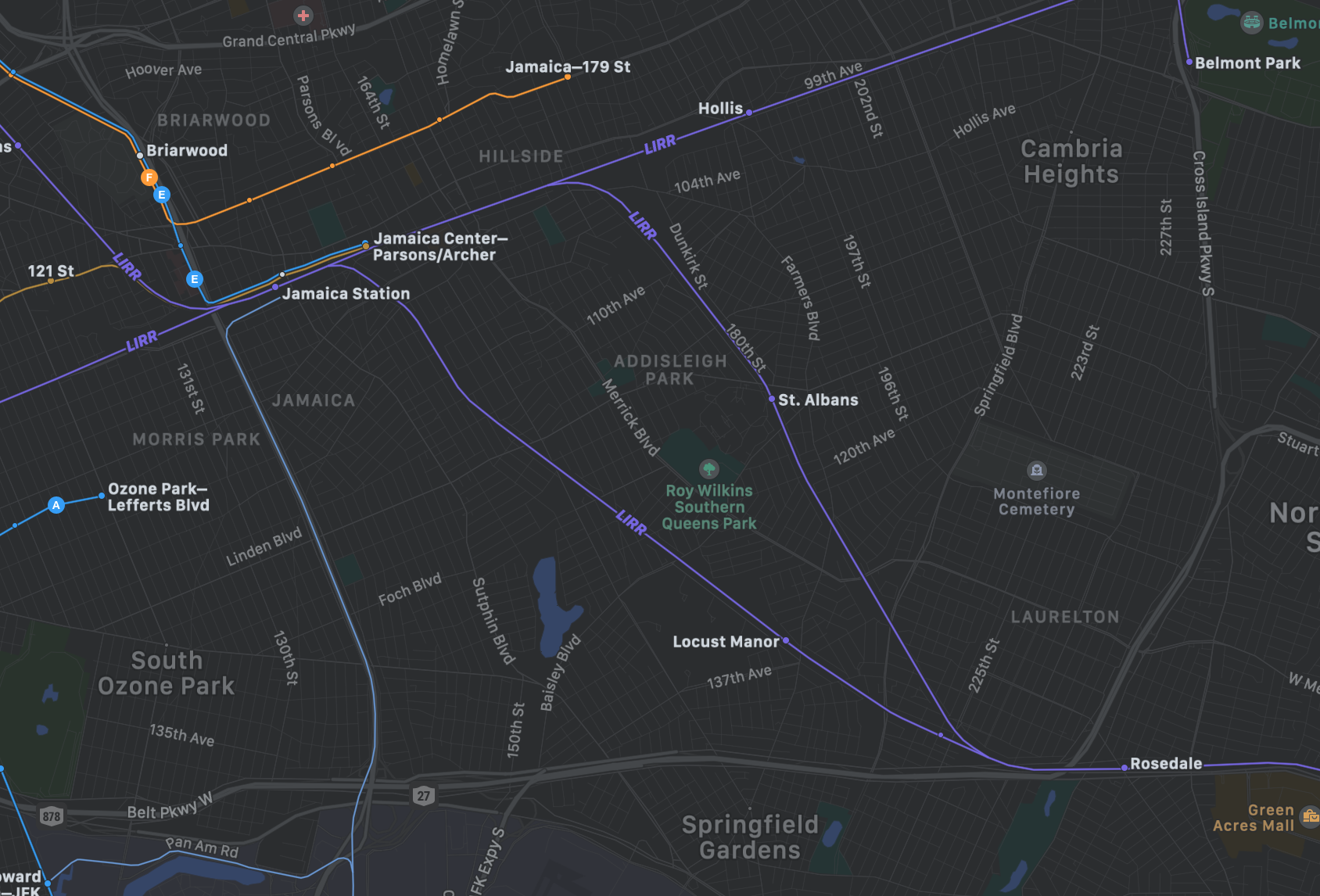

As for the IND, the line the line stemmed from a Second System provision which had been built during construction of the Queens Blvd Line in the late ‘30s, southeast (railroad north) of the Briarwood station. Originally intended for a subway extension under the Van Wyck Expressway, the provision extended as a lower level tunnel most of the way to the new Jamaica—Van Wyck station, before dead ending. The newer tunnel (constructed in the ‘70s-’80s) consists of a diamond crossover (X track) just before going into the new Van Wyck station. From there, the extension curves east to Archer Ave, becoming the upper level. The upper level continues as tail tracks after the terminal station at Parsons, curving south as a provision for a future extension down the LIRR Atlantic Branch right of way, through the now underserved southeast Queens.

The tunnels are relatively clean, as should e expected with their age, and feature different methods of construction. Some segments of the extension were constructed using the tunneling shield technique of deep bore tunneling—intended to minimize disturbance to the neighborhood. This is the source of the interesting round structure of some segments of the tunnel. However, most of the extension was built with the standard cut-and-cover method.